Media Literacy for Revolution

How you can better understand what you see online in 5 steps

Remember, if you will. September of 2019. A viral Facebook joke urged thousands to “Storm Area 51, They can’t stop all of us.”

30,000 people RSVP-ed online, and around 6,000 people traveled to the Nevada desert, according to a spokesperson. Some camped out for weeks.

I sent plenty of “When I get my alien from Area-51” memes to friends, and family.

It is obvious that information online can influence huge groups of people. So it’s more important than ever to understand and practice media literacy.

Media literacy is a fairly new concept, addressed at the National Leadership Conference on Media Literacy in 1993. The groups’ representatives settled on a basic definition of media literacy: it is the ability of a citizen to access, analyze and produce information for specific outcomes.

Nowadays, nearly everyone in developed nations has access to the internet, a never-ending trove of information.

At the time of filming, the United States experienced 197,000 deaths in total from COVID-19, according to the CDC. Each day, data trackers from the CDC, Google, The SF Chronicle and thousands of others give instant updates on the virus worldwide.

Amid the pandemic, global movements to end the systemic oppression of Black people are met with violence and misinformation. Fox News was called out in June for publishing digitally altered images of a Black Lives Matter protest in Seattle. Meanwhile Youtuber Zoe Amira created a video monetizing Google AdSense revenue as donations to BLM, totalling over $45 thousand.

What, and who, can we trust? How can we help? These issues apply to all people, not just journalists like me and my team.

So here are five steps to building your media literacy skills. These are meant to be done in order; if you can’t finish one step, you can’t move on to the next.

- Trust your instincts, Trust your gut

- Find the source

- Check their reputation

- See previous work, Ask what’s missing

- Choose to share, subscribe or ignore

It is easy to get lost in a forest of information. These steps can make reading the trail markers a bit easier.

Trust your instincts, trust your gut

This is the first step toward better media literacy. If something feels off, it’s a good idea to look further into it. Some headlines can be sensational or overly dramatic, like this: (screencap)

Some videos or photos may claim that something outrageous is the truth, like this:

If even a small part of you thinks, “Hmm. That’s weird,” let me tell you, it’s likely untrue or heavily skewed to appeal to a certain audience.

This is Eric Deggans, a TV critic at NPR who recently celebrated 30 years in the business.

“What I’m constantly trying to do, in fact, is educate my audience as to how media is speaking to why certain media projects are constructed the way they are, or why the media business does what it does,” Deggans said.

According to Deggans, all media is filled with overt messages and subtextural messages—those you can easily perceive and those that are harder to notice.

If you see a video online that states “This is what the media isn’t telling you!” or “See how overweight these child stars now are,” many of us feel the urge to click on the link, but we have a sinking feeling that something isn’t right.

Deggans educates people on how media works, to think critically about why stories are one way or the other and what the consequences of those decisions may be.

To sum up this step as easy as possible: Go with your gut. And if you feel like you are reading, watching or hearing legitimate facts, move on to the next step.

Find the source

This step seems simple, but can be deceptively difficult when you are critiquing media.

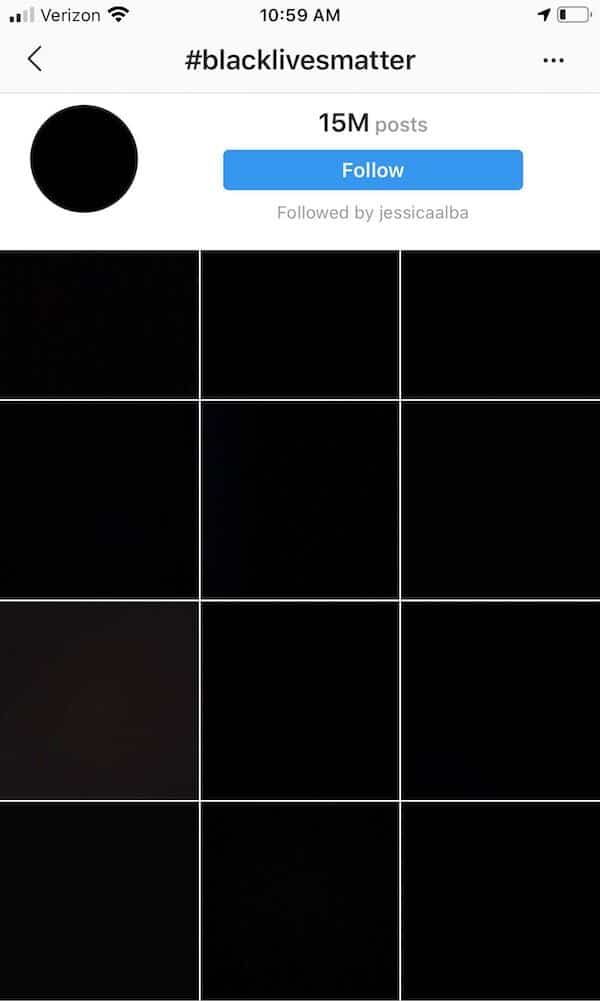

For an example, let’s address the “Blackout Tuesday” Instagram trend from June.

Well-meaning Instagram users posted black squares on their feeds in order to show support for the Black Lives Matter movement, and their fight for retribution for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Brayla Stone and so many other Black lives lost to systemic violence.

That day, important information about protests, aid and bail funds were blacked out by the trend. The #BLM showed thousands of black squares—effectively burying organizers’ work.

Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang, two Black women who work in music marketing, created the original blackout, under the hashtag “TheShowMustBePaused”, but that specifically referred to Black people in the music industry not getting recognition for their work.

There is no consensus on where the trend came from; that morning, it just seemed everyone had jumped on.

Celebrities often have a lot of pull on what people determine is legit online, and many posted black squares, apologizing after the situation became more complicated.

The conflict of those continuing to post black squares, those claiming the squares were detrimental to the movement, and the organizers struggling to promote their efforts covered social media for days afterward.

The lesson I learned is to find who made the media. On Instagram or Twitter, see if you can find the profile the post originated from. if it’s a page from Google search, find who wrote or produced it and if they have a biography on the site.

If you can’t find a byline, who wrote it, it’s likely fake. If the website isn’t available or the link doesn’t work, it’s put there to distract you.

Or if there are multiple sources saying the same thing and you can’t find where it came from, don’t trust it.

Check their reputation

An important part of media literacy is engaging with media from many different perspectives.

Dr. Tara Pixley is a professor of visual journalism and critical and ethical issues in journalism at Loyola Marymount University.

Pixley mostly freelances, like for the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, and was a photo editor for Newsweek Magazine in New York. She was also one of my first journalism professors.

As a queer Black woman and a first-generation American, Pixley works in many different genres of media to diversify different spaces between the journalism and academic realms.

“I think having an expansive diet of news media that includes viewpoints other than your own is imperative for you to understand the reality of a situation,” Pixley said. “When I look at them, when I look at what Fox News says about the Black Lives Matter protests, then a couple things are possible.

“One, I understand what another subset of America is reading and how they perceive what’s happening. Two, It informs my practice as a journalist, because I understand that I’m telling the story as I see it, but I’m also telling a story that is in relationship to other stories that exist,” Pixley said.

In the 2018 study “Third person effects of fake news: Fake news regulation and media literacy interventions,” authors S. Mo-Jang and Joon K. Kim define and address something called “Third-Person Perspective,” or “TPP.”

This refers to the perceptual gap where people perceive other political groups as being more influenced by fake news than their own political groups.

When my uncles say, “nothing on Fox News is real, and anyone who watches it is an idiot,” it matches the other side saying, “anyone reading the New York Times is a snowflake.”

For this step, you don’t have to agree with what the source stands for, but it’s better to know what they make for which audience.

See previous work, ask what’s missing

This step is my favorite, as I am known to dive down rabbit holes of online research, or Reddit threads of “Parks and Recreation” memes.

Christie Roschke is the managing director of a project at Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communicationat Arizona State University called the News Co/Lab. Her team works with newsrooms and journalists on ways that they can be more transparent and engage with their audiences about their work.

Roschke addressed the age-old journalist goal of “objectivity”

“That false notion of balance, we refer to that as like the two sides fallacy as though there are actually two equal sides, which maybe isn’t the case in some things, but for a lot of things, there really aren’t two equal sides,” Roschke said.

The journalism world is now increasingly acknowledging that there is no such thing as completely objective reporting, since every reporter and every publication is speaking from a different perspective. There are never only two sides to a story, but rather an infinite amount that each person, publication and media outlet approaches differently.

So when looking into a piece of media, Roschke suggested doing a simple Google search, using some keywords that can direct your search. She said if something is happening, it’s likely multiple news organizations have already reported on the subject.

“You know, this can take 30 seconds, maybe a minute tops. and you’ve just given yourself that peace of mind without having to investigate every nook and cranny of everything, because you know, most people are not going to do that,” Roschke said.

This step takes the longest amount of time, finding what a bunch of other sources are saying about a topic and asking what else you want to know. Does this story about the queer experience fail to include queer voices? Does this video about elderly Black folks in nursing homes include the necessary data?

But as with every skill, with time you become faster and faster and more adept at figuring out what’s been said and what hasn’t.

Share, subscribe or ignore

If you’ve made it this far, the piece of media you’re critiquing is either impressively thorough or totally bogus.

Now comes the fun part. With all the critical thinking you’ve done on the information, it is your decision what to do with it.

“You know, what the, there’s a lot of power that’s been given to the consumer in today’s media structure, both because you have so much choice between different news and media outlets, and because you’ve never had greater ability to express what you think about what they’re doing,” Eric Deggans from NPR said.

I like to simplify this step to three options:

- Share the information by posting on social media or engaging in conversations with your community.

- If you appreciate the work and want to support the publishers, subscribe to the content. News, videos, photos, shows, all of these forms of media cost money and time to produce. While paywalls can be frustrating or inaccessible for some, paying for content ensures that the content will continue and those working hard to produce it will get paid.

- If the information is bogus, sensational, or just fake, you can just plain ignore it. I usually chuckle a little and think to myself, “Wow, dodged that bullet. Now I’ll move to the next piece of media, or I’ll go play with my cat.”

“These spaces are really useful if we make them useful. These conversations are really productive if we let them be. And if we are engaging in that critical media conversation, we become better as a public; we become better as individuals,” Dr. Tara Pixley said.

“When we don’t do that work, then the opposite becomes true. We don’t understand our world as well. We don’t understand each other as well. we don’t really know what’s happening. We feel scared, we feel alone. We feel confused all the time. Because we can’t determine what is real, what is factual, and what is important.”